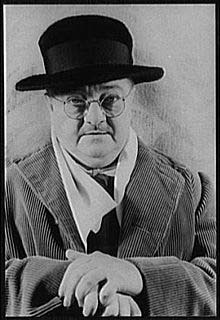

Typed Letter signed by Alexander Woolcott

Inv# AU1386

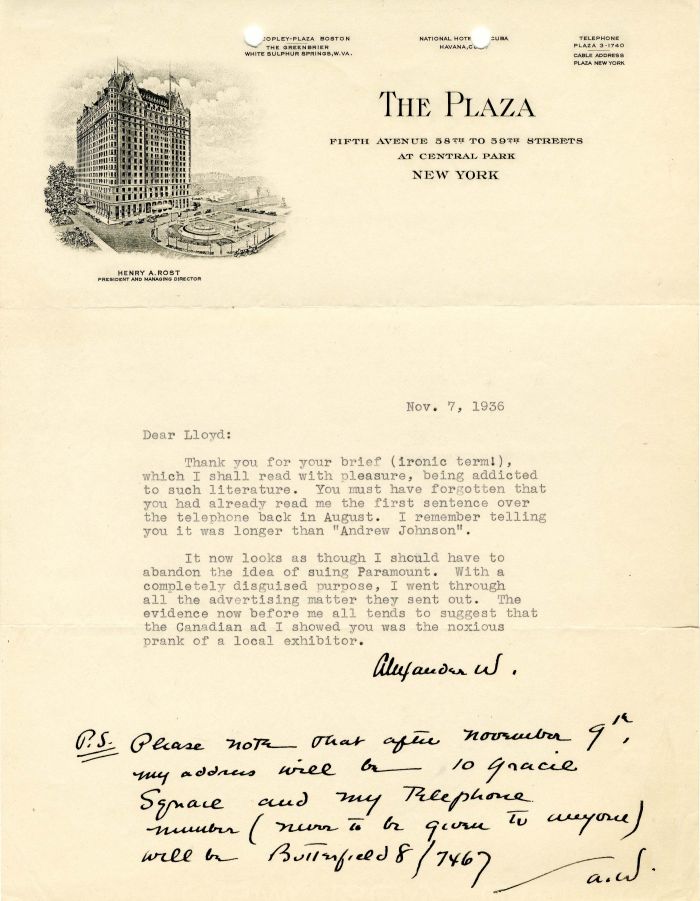

Typed letter on Plaza letterhead signed by Alexander W.

Alexander Humphreys Woollcott (January 19, 1887 – January 23, 1943) was an American critic and commentator for The New Yorker magazine and a member of the Algonquin Round Table. He was the inspiration for Sheridan Whiteside, the main character in the play The Man Who Came to Dinner (1939) by George S. Kaufman and Moss Hart, and for the far less likable character Waldo Lydecker in the film Laura (1944). Woollcott was convinced he was the inspiration for his friend Rex Stout's brilliant, eccentric detective Nero Wolfe, an idea that Stout denied. Alexander Woollcott was born in an 85-room house, a vast ramshackle building in Colts Neck Township, New Jersey. Known as "the North American Phalanx", it had once been a commune where many social experiments were carried on in the mid-19th century, some more successful than others. When the Phalanx fell apart after a fire in 1854, it was taken over by the Bucklin family, Woollcott's maternal grandparents. Woollcott spent large portions of his childhood there among his extended family. His father was a ne'er-do-well Cockney who drifted through various jobs, sometimes spending long periods away from his wife and children. Poverty was always close at hand. The Bucklins and Woollcotts were avid readers, giving young Aleck (his nickname) a lifelong love of literature, especially the works of Charles Dickens. He also resided with his family in Philadelphia, where he attended Central High School (110th Class), where a teacher, Sophie Rosenberger, reportedly "inspired him to literary effort" and with whom he "kept in touch all her life." With the help of a family friend, he made his way through college, graduating from Hamilton College, New York, in 1909. Despite a rather poor reputation (his nickname was "Putrid"), he founded a drama group, edited the student literary magazine, and was accepted by a fraternity (Theta Delta Chi). In his early twenties he contracted the mumps, which apparently left him mostly, if not completely, impotent. He never married or had children, although he had some notable female friends, including Dorothy Parker and Neysa McMein, to whom he reportedly proposed the day after she had just wed her new husband, Jack Baragwanath. Woollcott once told McMein that “I’m thinking of writing the story of our life together. The title is already settled.” McMein: “What is it?” Woollcott: “Under Separate Cover.” Woollcott joined the staff of The New York Times as a cub reporter in 1909. In 1914 he was named drama critic and held the post until 1922, with a break for service during World War I. In April 1917, the day after war was declared, Woollcott volunteered as a private in the medical corps. Posted overseas, Woollcott was a sergeant when the intelligence section of the American Expeditionary Forces selected him and a half-dozen other newspaper men to create the Stars and Stripes, an official newspaper to bolster troop morale. As chief reporter for the Stars and Stripes, Woollcott was a member of the team that formed its editorial board. These included Harold Ross, founder of The New Yorker magazine; Cyrus Baldridge, multifaceted illustrator, author and writer; and the future columnist and radio personality, Franklin P. Adams. Going beyond simple propaganda, Woollcott and his colleagues reported the horrors of the Great War from the point of view of the common soldier. After the war he returned to The New York Times, then transferred to the New York Herald in 1922 and to The World in 1923. He remained there until 1928. One of New York's most prolific drama critics, he was banned for a time from reviewing certain Broadway theater shows due to his florid and often vitriolic prose. He sued the Shubert theater organization for violation of the New York Civil Rights Act, but lost in the state's highest court in 1916 on the grounds that only discrimination on the basis of race, creed or color was unlawful. From 1929 to 1934, he wrote a column called "Shouts and Murmurs" for The New Yorker. His book, While Rome Burns, published by Grosset & Dunlap in 1934, was named twenty years later by critic Vincent Starrett as one of the 52 "Best Loved Books of the Twentieth Century." Woollcott's review of the Marx Brothers' Broadway debut, I'll Say She Is, helped the group's career inflate from mere success to superstardom and started a lifelong friendship with Harpo Marx. Harpo's two adopted sons, Alexander Marx and William (Bill) Woollcott Marx, were named after Woollcott and his brother, Billy Woollcott.

Ebay ID: labarre_galleries