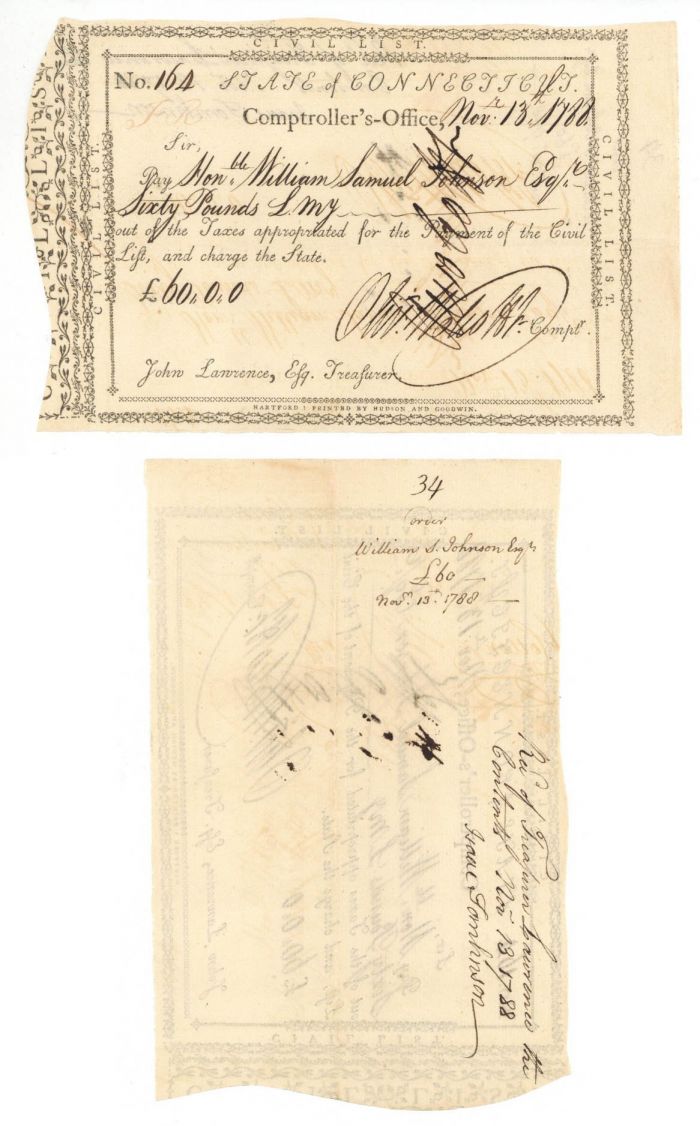

1788 dated Pay Order Issued to William Samuel Johnson and signed by him and Oliver Wolcott Jr. - Connecticut Revolutionary War Bonds

Inv# CT1109 Autograph

State of Connecticut Pay Order issued to William Samuel Johnson and signed by him on back. Also signed twice by Oliver Wolcott Jr. on front.

Oliver Wolcott Jr. (January 11, 1760 – June 1, 1833) was an American politician and judge. He served as the second United States Secretary of the Treasury, a judge on the United States Circuit Court for the Second Circuit, and the 24th Governor of Connecticut. Wolcott began his adult life working in Connecticut, later joining the federal government in the Department of Treasury, before returning to Connecticut, where he spent the remainder of his life until his death. Over the course of his political career, Wolcott's views shifted from Federalist to Toleration and ultimately to Jacksonian. He was the son of Oliver Wolcott Sr. and was part of the Griswold-Wolcott family.

Born on January 11, 1760, in Litchfield, Connecticut Colony, British America, Wolcott served in the Continental Army from 1777 to 1779 during the American Revolutionary War. He graduated from Yale University in 1778, where he was a member of the Brothers in Unity society, and studied law in 1781.

Before becoming the second Secretary of Treasury, Wolcott was the first Auditor in the Treasury Department. According to Richard White, his duties as Auditor involved making the initial examination of accounts and determining balances on all claims against the government. Working alongside the first Secretary of Treasury, Alexander Hamilton, and as a fellow Federalist, Wolcott became a target for criticism from Thomas Jefferson. This was due to the rivalry between Hamilton's Federalists and Jefferson's Democratic-Republicans, who were the two main political factions of the time.

William Samuel Johnson (October 7, 1727 – November 14, 1819) was a prominent American Founding Father and statesman. Prior to the Revolutionary War, he held the position of militia lieutenant but was later relieved of his duties after declining his election to the First Continental Congress. He is recognized for his signature on the United States Constitution, his representation of Connecticut in the United States Senate, and his role as the third president of King's College, which is now known as Columbia University.

Born in Stratford, Connecticut, on October 7, 1727, Johnson was the son of Samuel Johnson, a distinguished Anglican clergyman and the founding president of King's College, and his first wife, Charity Floyd Nicoll. He received his early education at home before graduating from Yale College in 1744, subsequently earning a master's degree from the same institution in 1747, along with an honorary degree from Harvard in that same year.

Despite his father's encouragement to enter the clergy, Johnson chose to pursue a career in law. He educated himself in legal matters and quickly built a significant clientele, establishing business relationships that extended beyond his home colony. Additionally, he served in the Connecticut colonial militia for over two decades, achieving the rank of colonel. Johnson was also active in the Connecticut Legislature, serving in the lower house in 1761 and 1765, and in the upper house from 1766 and again from 1771 to 1775. Furthermore, he was a member of the colony's Supreme Court from 1772 to 1774.

Ebay ID: labarre_galleries