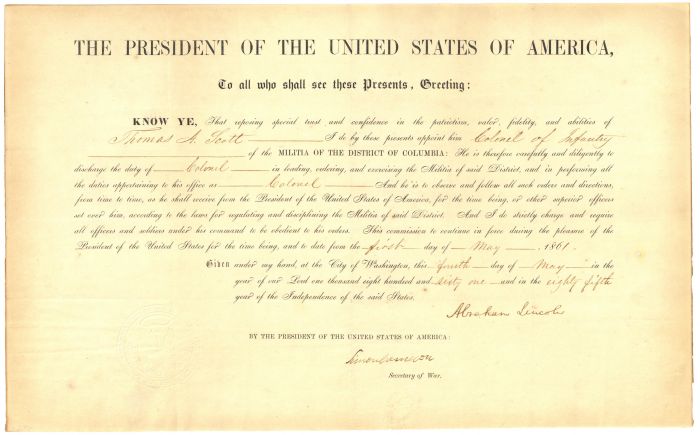

Abraham Lincoln signed Appointment to Thomas A. Scott

Inv# AG2089Signed by Abraham Lincoln. Also signed by Simon Cameron. Abraham Lincoln, a self-taught lawyer, legislator and vocal opponent of slavery, was elected 16th president of the United States in November 1860, shortly before the outbreak of the Civil War. Lincoln proved to be a shrewd military strategist and a savvy leader: His Emancipation Proclamation paved the way for slavery’s abolition, while his Gettysburg Address stands as one of the most famous pieces of oratory in American history. In April 1865, with the Union on the brink of victory, Abraham Lincoln was assassinated by Confederate sympathizer John Wilkes Booth. Lincoln’s assassination made him a martyr to the cause of liberty, and he is widely regarded as one of the greatest presidents in U.S. history.

Abraham Lincoln's Early Life

Lincoln was born on February 12, 1809 to Nancy and Thomas Lincoln in a one-room log cabin in Hardin County, Kentucky. His family moved to southern Indiana in 1816. Lincoln’s formal schooling was limited to three brief periods in local schools, as he had to work constantly to support his family.

In 1830, his family moved to Macon County in southern Illinois, and Lincoln got a job working on a river flatboat hauling freight down the Mississippi River to New Orleans. After settling in the town of New Salem, Illinois, where he worked as a shopkeeper and a postmaster, Lincoln became involved in local politics as a supporter of the Whig Party, winning election to the Illinois state legislature in 1834.

Lincoln taught himself law, passing the bar examination in 1836. The following year, he moved to the newly named state capital of Springfield. For the next few years, he worked there as a lawyer and serving clients ranging from individual residents of small towns to national railroad lines.

He met Mary Todd, a well-to-do Kentucky belle with many suitors (including Lincoln’s future political rival, Stephen Douglas), and they married in 1842. The Lincolns went on to have four children together, though only one would live into adulthood: Robert Todd Lincoln (1843–1926), Edward Baker Lincoln (1846–1850), William Wallace Lincoln (1850–1862) and Thomas “Tad” Lincoln (1853-1871).

Abraham Lincoln Enter Politics

Lincoln won election to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1846 and began serving his term the following year. As a congressman, Lincoln was unpopular with many Illinois voters for his strong stance against the Mexican-American War. Promising not to seek reelection, he returned to Springfield in 1849.

Events conspired to push him back into national politics, however: Douglas, a leading Democrat in Congress, had pushed through the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act (1854), which declared that the voters of each territory, rather than the federal government, had the right to decide whether the territory should be slave or free.

On October 16, 1854, Lincoln went before a large crowd in Peoria to debate the merits of the Kansas-Nebraska Act with Douglas, denouncing slavery and its extension and calling the institution a violation of the most basic tenets of the Declaration of Independence.

With the Whig Party in ruins, Lincoln joined the new Republican Party–formed largely in opposition to slavery’s extension into the territories–in 1856 and ran for the Senate again that year (he had campaigned unsuccessfully for the seat in 1855 as well). In June, Lincoln delivered his now-famous “house divided” speech, in which he quoted from the Gospels to illustrate his belief that “this government cannot endure, permanently, half slave and half free.”

Lincoln then squared off against Douglas in a series of famous debates; though he lost the Senate election, Lincoln’s performance made his reputation nationally.

Abraham Lincoln’s 1860 Presidential Campaign

Lincoln’s profile rose even higher in early 1860, after he delivered another rousing speech at New York City’s Cooper Union. That May, Republicans chose Lincoln as their candidate for president, passing over Senator William H. Seward of New York and other powerful contenders in favor of the rangy Illinois lawyer with only one undistinguished congressional term under his belt.

In the general election, Lincoln again faced Douglas, who represented the northern Democrats; southern Democrats had nominated John C. Breckenridge of Kentucky, while John Bell ran for the brand new Constitutional Union Party. With Breckenridge and Bell splitting the vote in the South, Lincoln won most of the North and carried the Electoral College to win the White House.

He built an exceptionally strong cabinet composed of many of his political rivals, including Seward, Salmon P. Chase, Edward Bates and Edwin M. Stanton.

Lincoln and the Civil War

After years of sectional tensions, the election of an antislavery northerner as the 16th president of the United States drove many southerners over the brink. By the time Lincoln was inaugurated as 16th U.S. president in March 1861, seven southern states had seceded from the Union and formed the Confederate States of America.

Lincoln ordered a fleet of Union ships to supply the federal Fort Sumter in South Carolina in April. The Confederates fired on both the fort and the Union fleet, beginning the Civil War. Hopes for a quick Union victory were dashed by defeat in the Battle of Bull Run (Manassas), and Lincoln called for 500,000 more troops as both sides prepared for a long conflict.

While the Confederate leader Jefferson Davis was a West Point graduate, Mexican War hero and former secretary of war, Lincoln had only a brief and undistinguished period of service in the Black Hawk War (1832) to his credit. He surprised many when he proved to be a capable wartime leader, learning quickly about strategy and tactics in the early years of the Civil War, and about choosing the ablest commanders.

Abraham Lincoln’s Assassination

On the night of April 14, 1865 the actor and Confederate sympathizer John Wilkes Booth slipped into the president’s box at Ford’s Theatre in Washington, D.C., and shot him point-blank in the back of the head. Lincoln was carried to a boardinghouse across the street from the theater, but he never regained consciousness, and died in the early morning hours of April 15, 1865.

Lincoln’s assassination made him a national martyr. On April 21, 1865, a train carrying his coffin left Washington, D.C. on its way to Springfield, Illinois, where he would be buried on May 4. Abraham Lincoln’s funeral train traveled through 180 cities and seven states so mourners could pay homage to the fallen president.

Today, Lincoln’s birthday—alongside the birthday of George Washington—is honored on President’s Day, which falls on the third Monday of February.

Abraham Lincoln Quotes

“Nothing valuable can be lost by taking time.”

“I want it said of me by those who knew me best, that I always plucked a thistle and planted a flower where I thought a flower would grow.”

“I am rather inclined to silence, and whether that be wise or not, it is at least more unusual nowadays to find a man who can hold his tongue than to find one who cannot.”

“I am exceedingly anxious that this Union, the Constitution, and the liberties of the people shall be perpetuated in accordance with the original idea for which that struggle was made, and I shall be most happy indeed if I shall be an humble instrument in the hands of the Almighty, and of this, his almost chosen people, for perpetuating the object of that great struggle.”

“This is essentially a People's contest. On the side of the Union, it is a struggle for maintaining in the world, that form, and substance of government, whose leading object is, to elevate the condition of men -- to lift artificial weights from all shoulders -- to clear the paths of laudable pursuit for all -- to afford all, an unfettered start, and a fair chance, in the race of life.”

“Fourscore and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent a new nation, conceived in liberty and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.”

“This nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom — and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.”

Simon Cameron

(March 8, 1799 – June 26, 1889) was an American businessman and politician. He represented Pennsylvania in the United States Senate and served as United States Secretary of War under President Abraham Lincoln at the start of the American Civil War.

Born in Maytown, Pennsylvania, Cameron made a fortune in railways, canals, and banking. As a member of the Democratic Party, he won election to the Senate in 1845, serving until 1849. A persistent opponent of slavery, Cameron briefly joined the Know Nothing Party before switching to the Republican Party in 1856. He won election to another term in the Senate in 1857 and sought the Republican presidential nomination at the 1860 Republican National Convention. After the convention's first ballot, Cameron withdrew his name from consideration in favor of Lincoln, who went on to win the Republican nomination.

After Lincoln won the presidential election of 1860, he appointed Cameron as his first Secretary of War. Cameron's tenure was marked by allegations of corruption and lax management, and he was forced to resign in January 1862. He briefly served as the U.S. ambassador to Russia later that year. Cameron made a political comeback after the Civil War, winning election to the Senate in 1867. Cameron built a powerful state party machine that would dominate Pennsylvania politics for the next seventy years. He served in the Senate until 1877, when he was succeeded by his son, J. Donald Cameron.

According to historian Hans L. Trefousse, Cameron ranks as one of the most successful political bosses in American history. It was shrewd, wealthy, and devoted his talents in money to the goal of building a powerful Republican organization. He achieved recognition as the undisputed arbiter of Pennsylvania politics. His assets included business acumen, sincere devotion to the interests and needs of Pennsylvania, expertise on the tariff issue and the need for protection for Pennsylvania industry, and a skill at managing and organizing politicians and their organizations. He cleverly rewarded his friends, punished his enemies, and maintain good relations with his Democratic counterparts. His reputation as an unscrupulous grafter was exaggerated by his enemies; he was in politics for power, not profit.

As a young man his prudent investments in publishing, banking, manufacturing and railroads provided both a financial bankroll, and wide insights into key industries that boosters across Pennsylvania wanted to support. Originally an anti-abolitionist Democrat, Cameron moved to the Whig party by the mid-1840s. When the Democrats factionalized in 1845, he joined with insurgent Democrats and mainline Whigs to win election to the Senate. Again in 1857 he put together a coalition of Republicans, Know Nothings, and Democratic insurgents to win the legislatures vote for Senator. He waged a bitter dispute with governor-elect Andrew Curtin, but nevertheless it 1860 made himself the state's favorite son at the Republican national convention. He was not a serious contender for the presidency, but his control of the Pennsylvania delegation gave him a lock on a high position Lincoln's cabinet. Cameron was a poor secretary of war, unable to deal with the small-mindedness, the inefficiencies, and the fraud that pervaded contracts. He had little sense of national politics or military strategy. Biographer Paul Kahan says he was very good as a “back-slapping, glad-handing politician,” who could manipulate congressmen. But he was too disorganized, and inattentive to the extremely complex duties of the largest and most important federal department. He paid too much attention to patronage and then not enough to strategy. He broke with Lincoln and openly openly advocated Emancipating the slaves and arming them for the Army at a time Lincoln was not ready to publicly Take that position. Lincoln sent him to Russia but continued to consult him. After the war, Cameron became the state party boss, returning to the Senate in 1867 and perfecting his machine. He used highly able lieutenants including Matthew Quay. Robert W. Mackey and his son Donald Cameron. In national politics he was a Radical Republican who opposed President Andrew Johnson and became a key advisor to President Ulysses Grant. President Rutherford Hayes dislike Cameron, but was outmaneuvered.

THOMAS ALEXANDER SCOTT

Thomas Alexander Scott (December 28, 1823 – May 21, 1881) was an American businessman, railroad executive, and industrialist. President Abraham Lincoln in 1861 appointed him to serve as U.S. Assistant Secretary of War, and during the American Civil War railroads under his leadership played a major role in the war effort. He became the fourth president of the Pennsylvania Railroad (1874–1880), which became the largest publicly traded corporation in the world and received much criticism for his conduct in the Great Railway Strike of 1877 and as a "robber baron." Scott helped negotiate the Republican Party's Compromise of 1877 with the Democratic Party; it settled the disputed presidential election of 1876 in favor of Rutherford B. Hayes in exchange for the federal government pulling out its military forces from the South and ending the Reconstruction era. In his final years, Scott made large donations to the University of Pennsylvania.

Early life

Scott was born on December 28, 1823 in Peters Township near Fort Loudoun, in Franklin County, Pennsylvania. He was the 7th of eleven children.

Career

Railroads

Scott joined the Pennsylvania Railroad in 1850 as a station agent, and by 1858 was general superintendent. Scott had been recommended for promotion by Herman Haupt and later took a special interest in mentoring aspiring railroad employees, such as Andrew Carnegie (who joined the Pittsburgh telegraph office at age 16 and became Scott's private secretary and telegrapher).

The 1846 state charter to the Pennsylvania Railroad diffused power within the company, by giving executive authority to a committee responsible to stockholders, and not to individuals. By the 1870s, however, officers directed by J. Edgar Thomson (the Pennsylvania Railroad's President from 1852 until his death in 1874) and Scott had centralized power.

Historians have explained the successful partnership of Thomas Scott and J. Edgar Thomson by the melding of their opposing personality traits: Thomson was the engineer, cool, deliberate, and introverted; Scott was the financier, daring, versatile, and a publicity-seeker. In addition, they had common experiences and values, agreement on the importance of financial success, the financial stability of the Pennsylvania Railroad throughout their partnership, and J. Edgar Thomson's paternalism.

By 1860, when Scott became the first Vice President of the Pennsylvania Railroad, it had expanded from a company of railway lines within Pennsylvania through the 1840s and 1850s, to a transportation empire (which it would continue to expand under his guidance from the 1860s onward).

Civil War

At the outbreak of the American Civil War, Pennsylvania Governor Andrew Curtin called on Scott for his extensive knowledge of the rail and transportation systems of the state. In May 1861, Scott received a commission as Colonel of Volunteers and placed in command of railroad and telegraph lines used by the Union armies. His friend, Secretary of War Simon Cameron in August 1861 appointed him Assistant Secretary of War, and gave him responsibility for building a railroad through Washington D.C. to connect the Orange and Alexandria Railroad with northern railroads. Scott also advised creating transportation and telegraph bureaus and arranging draft exemptions for experienced civilian mechanics and locomotive engineers, for needed military railroad operations were compromised by the loss of experienced railroad men. The next year, despite Cameron's replacement by Edwin M. Stanton, Scott helped organize the Loyal War Governors' Conference in Altoona, Pennsylvania.

Later on, Scott took on the task of equipping a substantial military force for the Union war effort. He assumed supervision of government railroads and other transportation lines. He made the movement of supplies and troops more efficient and effective for the war effort on behalf of the Union. In one instance, he engineered the movement of 25,000 troops in 24 hours from Nashville, Tennessee, to Chattanooga, turning the tide of battle to a Union victory.

Scott also advised President Lincoln to travel covertly by rail to avoid Confederate spies and assassins.

Reconstruction era

Scott invested in oil exploration around the Ojai, California area, sending his nephew Thomas Bard to drill oil seeps noted by Benjamin Silliman. Bard produced California's first oil gusher in 1867.

During the American Reconstruction in the aftermath of the Civil War, the Southern states needed their economy and infrastructure restored, and more investment in railroads. They had lagged behind the North in railroad miles. The Northern-based railroads competed to acquire routes and construct rail lines in the South. Federal assistance was sought by both special interest groups, but the Crédit Mobilier of America scandal made this difficult in 1872. Congress became unwilling to grant railroad companies land grants in the Southwestern United States. Mindful of the corruption allegations which had dogged his friend Cameron, Scott was notoriously secretive about his business dealings, conducting most of his business in private letters, and instructing his business partners to destroy them after they were read. After the Civil War, Scott was heavily involved in investments in the fast-growing trans-Mississippi River route into Texas, with long-term plans for a southern transcontinental railway line connecting the Southern states and California. From 1871 to 1872, Scott was briefly the president of the Union Pacific Railroad, then the first transcontinental railroad owner. He was the president of the Pennsylvania Railroad from 1874, upon the death of his partner Thomson, until 1880. The financial Panic of 1873 and subsequent economic depression made it impossible to finance Scott's southern transcontinental railroad plans.

In his "Scott Plan" of the later 1870s, Scott proposed that the largely Democratic Southern politicians would give their votes in Congress and state legislatures for federal government subsidies to various infrastructure improvements, including in particular the Texas and Pacific Railway, which Scott headed. Scott employed the expertise of Grenville Dodge in buying the support of newspaper editors as well as various politicians to build public support for the subsidies. The Scott Plan became part of the Compromise of 1877, an informal and unwritten deal which settled the disputed Presidential election of 1876. However, it was never implemented. Railroad construction in the South remained at a low level after 1873 and its financial panic.

Great Railroad Strike of 1877

Despite Scott's best efforts, the Pennsylvania Railroad continued to lose money through the 1870s. Oil magnate John D. Rockefeller had shifted much of his transportation of product for Standard Oil to his pipelines, causing severe problems for the rail industry. Scott still controlled the railway to Pittsburgh, where the pipelines of Rockefeller did not extend, but the two men were unable to come to terms on transportation costs. In response, Rockefeller closed his plants in Pittsburgh, forcing Scott to enact aggressive pay deductions of workers.

In reaction, railroad workers went off the job and rioted in Pittsburgh; the city was the epicenter of the worst violence in the nation during the Great Railroad Strike of 1877. Scott, often referred to as one of the first robber barons of the Gilded Age, was quoted as saying that the strikers should be given "a rifle diet for a few days and see how they like that kind of bread." According to historian Heather Cox Richardson, Scott convinced President Hayes to use federal troops to end the strike, providing motivation for the Posse Comitatus Act of 1878.

Death and legacy

Like his counterpart John Work Garrett of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, Scott never recovered from the 1877 strike. Scott's crucial business partner, John Edgar Thomson, had died in 1874. Scott suffered a stroke in 1878, limiting his ability to work. He died on May 21, 1881, and was buried at Woodlands Cemetery in Philadelphia.

The railroad-based economy of the United States was overtaken by the oil boom. Scott's protege Andrew Carnegie later challenged the Rockefeller monopoly in petroleum from his dominance of the steel industry. Just as the economy of railroads gave way to that of oil, oil in turn would face the emerging dominance of steel. During the American Civil War, the Union named a steam transport Thomas A. Scott to honor Scott. Ironically, Dr. Samuel Mudd, who had assisted President Lincoln's assassins, used it during his attempted escape from Fort Jefferson, Florida. Interested in education and health, Scott endowed certain positions at the University of Pennsylvania. His widow also made a variety of endowments in his name at the University of Pennsylvania, including:

Thomas A. Scott Fellowship in Hygiene

Thomas A. Scott Professorship of Mathematics

University Hospital: endowed beds for patients with chronic diseases.

Ebay ID: labarre_galleries