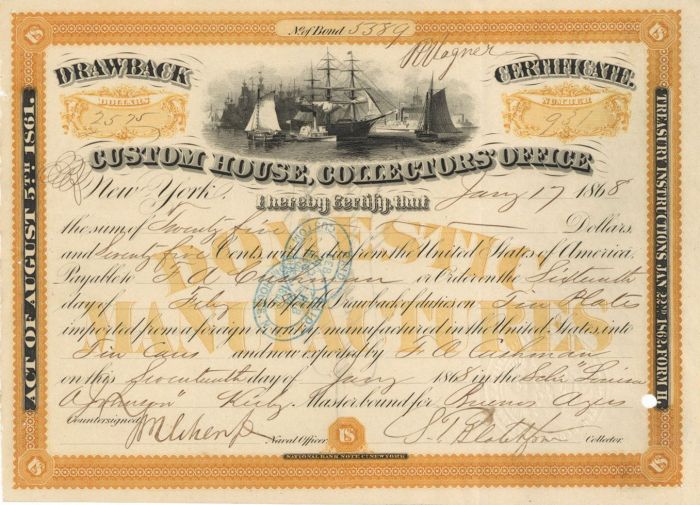

Custom House, Collector's Office - Shipping Drawback Bond Certificate

Inv# SS1325 Stock

Bond printed by National Bank Note Co., New York. Gorgeous!

The Alexander Hamilton U.S. Custom House is a government building and former custom house at 1 Bowling Green, near the southern end of Manhattan in New York City. Designed by Cass Gilbert in the Beaux-Arts style, it was erected from 1902 to 1907 by the U.S. government as a headquarters for the Port of New York's duty collection operations. The building contains the George Gustav Heye Center museum, the United States Bankruptcy Court for the Southern District of New York, and offices for the National Archives. The facade and part of the interior are New York City designated landmarks, and the building is a National Historic Landmark listed on the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP). The building is also a contributing property to the Wall Street Historic District, listed on the NRHP.

The Custom House is a seven-story steel-framed structure with a stone facade and elaborate interiors. The exterior is decorated with nautical motifs, as well as sculptures by twelve artists. The second through fourth stories contain colonnades with Corinthian columns. The main entrance consists of a grand staircase flanked by Four Continents, a set of four statues by Daniel Chester French. The second-story entrance vestibule leads to a transverse lobby, as well as a rotunda and offices. The rotunda includes a skylight and ceiling murals by Reginald Marsh. The ground floor contains museum space and loading docks, while the upper stories include offices.

The Custom House was proposed in 1889 as a replacement for the previous New York Custom House at 55 Wall Street. Due to various disagreements, the Bowling Green Custom House was not approved until 1899; Gilbert was selected as an architect following a competition. The building opened in 1907, and the murals in the rotunda were added in 1938 during a Works Progress Administration project. The United States Customs Service moved out of the building in 1974, and it remained vacant for over a decade until renovations in the late 1980s. The Custom House was renamed in 1990 to commemorate Alexander Hamilton, one of the Founding Fathers of the United States and its first Secretary of the Treasury. The George Gustav Heye Center, a branch of the National Museum of the American Indian, opened in the building in 1994.

The Alexander Hamilton U.S. Custom House occupies a trapezoidal plot bounded by Bowling Green to the north, Whitehall Street to the east, Bridge Street to the south, and State Street to the east. The Whitehall Street and State Street elevations are 300 feet (90 m) wide; the main elevation on Bowling Green is 200 feet (60 m) wide; and the rear elevation on Bridge Street is 290 feet (88 m) wide. Nearby buildings include the International Mercantile Marine Company Building and the Bowling Green Offices Building to the northwest, 26 Broadway to the northeast, 2 Broadway to the east, and One Battery Park Plaza to the south.

There are entrances to two New York City Subway stations immediately outside the Custom House. An entrance to the Whitehall Street station is adjacent to the eastern side of the building, while an entrance to the Bowling Green station is to the north. The building occupies the site of Fort Amsterdam, constructed by the Dutch West India Company to defend their operations in the Hudson Valley. The Dutch colony of New Amsterdam, the precursor to modern-day New York City, was developed around the fort. Bowling Green, immediately to the north, is the oldest park in New York City.

The Alexander Hamilton U.S. Custom House is seven stories high with a stone facade and an interior steel frame. It was designed by Cass Gilbert in the Beaux-Arts style. The design is similar to that of previous custom houses in New York City, namely Ithiel Town's Federal Hall at 26 Wall Street and Isaiah Rogers's Merchants' Exchange building at 55 Wall Street.

The building's design incorporates Beaux Arts and City Beautiful movement planning principles, combining architecture, engineering, and fine arts. Gilbert had written in 1900 about his plans for a wide-ranging, site-specific decorative program, which would "illustrate the commerce of ancient and modern times, both by land and sea". Sculptures, paintings, and decorations by well-known artists of the time, such as Daniel Chester French, Karl Bitter, Louis Saint-Gaudens, and Albert Jaegers, embellish various portions of the interior and exterior.

Unlike most custom houses, which face the waterfront, the Alexander Hamilton Custom House faces inland toward Bowling Green. The exterior is decorated throughout with nautical motifs such as dolphins and waves, interspersed with classical icons such as acanthus leaves and urns.

The first-floor facade is composed of rusticated blocks and is 20 feet (6.1 m) tall. There are six entrances to the building. The main entrance is on the northern elevation, where a wide stairway leads to the second floor. Under the main entrance arch is a carving of the municipal arms of the city of New York. The keystone at the top of the arch depicts the head of Columbia, the female personification of the United States, and was designed by Vicenzo Albani. Andrew O'Connor created a cartouche for the space above the main entrance. The lintel above the main entrance, quarried in Maine, weighed 50 short tons (45 metric tons) and measured 30 by 8 feet (9.1 by 2.4 m).

The second through fourth stories contain engaged columns in the Corinthian style; some of these columns are paired while the others are single. There are 44 columns in total: twelve each on the north, east, and west elevations and eight on the south elevation. The second story is the piano nobile; the windows on this story are flanked by brackets and capped by enclosed pediments, with carved heads above them (see § Sculptures). The third- and fourth-story windows, conversely, are less ornately decorated; this was normal for Beaux-Arts buildings, which generally had greater detailing on the more visible lower levels. The lintels above the third-story windows are decorated with wave motifs, while those above the fourth floor depict shells. The center portion of the Bridge Street facade reaches only to the third story.

The fifth-story facade consists of a full-story entablature with a frieze and short rectangular windows. The sixth story is directly above it, while the seventh story consists of a red-slate mansard roof with dormer windows and copper cresting. The mansard roof is extremely steep, allowing the seventh-story attic to be designed as a full floor of usable space.

Twelve sculptors were hired to create the figural groups on the exterior. The major work flanking the front steps, the Four Continents, was contracted to Daniel Chester French, who designed the sculptures with associate Adolph A. Weinman. The work was made of marble and sculpted by the Piccirilli brothers; each sculptural group cost $13,500 (equivalent to $281,003 in 2020). From east to west, the statues depict larger-than-life-size personifications of Asia, America, Europe, and Africa. The primary figure of each group is a woman and is flanked by smaller human figures. In addition, Asia's figure is paired with a tiger and Africa's figure is paired with a lion.

The capitals of each of the 44 columns are decorated with carved heads depicting Hermes, the Greek god of commerce. The windows on the main facade are topped by eight keystones, which contain carved heads with depictions of eight human races. One source described the keystones as representing "Caucasian, Hindu, Latin, Celt and Mongol, Italian, African, Eskimo, and even the Coureur de Bois".

Above the main cornice are a group of standing sculptures that personify seafaring nations. There are twelve such statues, which depict commercial hubs through both ancient and modern history. Each sculpture is 11 feet (3.4 m) tall and weighs 20 short tons (18 metric tons). These sculptures are arranged in chronological sequence from east to west, or from left to right as seen from directly in front of the building. The easternmost sculptures are of ancient Greece and Rome, while the westernmost sculptures are of the more recent French and British empires. Eight sculptors were commissioned for this work. One of these sculptures, Germania by Albert Jaegers, was modified in 1918 to display Belgian insignia rather than German insignia. Bitter created a cartouche of the United States' coat of arms for the roof.

A barrel-vaulted entrance vestibule, supported by marble columns and decorated with multicolored mosaics, is just inside the entrance. Behind bronze gates is a passageway to the Great Hall. At the center of the building is a double-height rotunda, rising to the third story. Stairways, made of marble with iron handrails, connect the interior spaces. There are elevators in each corner; the southwestern and southeastern banks contain two elevators each, while the northwestern and northeastern banks have three elevators apiece. The northwestern and northeastern elevators were originally open cages but were replaced with enclosed cabs in 1935.

Because the original appropriation was limited in scope, decorative elements in the initial construction were limited to several important rooms, including the rotundas, hallways, lobby, and collector's office. These spaces had marble walls in multiple hues, while nautical motifs were placed in numerous locations.

The second-floor ceiling is generally 23 feet (7.0 m) tall. It consists of the former office spaces in the front and rear, the transverse lobby, and the rotunda. Gilbert planned the Custom House's interior so "all entrances, corridors, stairways and passages [were] arranged on the most direct and simple axial lines". The second-floor space, including the former offices, is almost entirely occupied by the Heye Center of the National Museum of the American Indian.

The transverse lobby crosses the northern end of the second floor, from west to east. Generally, the more important offices were positioned north of the lobby, while divisions dealing in more routine work were relegated to the south. Following the second floor's conversion into the Heye Center, the former back offices have been occupied by various exhibition galleries, while the front offices house the museum store and a future cafe space.

Membrane arches divide the lobby into five bays. The floors are decorated in marble mosaic patterns. An entablature runs around the top of the lobby, with galleries on the third story. There are two doorways on the walls, each topped by carved architraves with nautical symbols. The doors from the lobby to the former offices are made of varnished oak and stippled glass. At the center of the lobby is a three-bay-wide foyer with a pair of round arches to the north and south, which are supplemented by green Doric-style marble columns with white capitals. The bays of the foyer are separated by marble piers. Three bronze lanterns are suspended from the vaulted ceiling, hanging above a red-marble disc on the floor. Elmer E. Garnsey designed murals for the ceiling.

Semicircular staircases, with bronze railings and marble stair treads, flank the lobby. The stairs do not have any metal support structures and are composed entirely of flat, hard-burned clay tiles. Under each stair are timbrel arches, which connect each landing. The stairs rise to the seventh floor, which contains a skylight that is meant to evoke the design of a ship's cabin. Only the western stair between the first and second floors is open to the public. The elevator doors in the lobby are topped by bronze transom grilles that depict a caravel or sailing ship.

The collector's office is at the northwestern corner of the second floor. The office contains elaborate hardwood floors and oak wainscoting designed by Tiffany Studios. Garnsey painted ten oil paintings, which are installed above the wainscoting. Each painting is surrounded by a gold frame and depicts a Dutch or English port in the New World. The office also included a stone fireplace mantel with a plaque referencing Fort Amsterdam and the Government House, which both had previously occupied the Custom House's site. The coffered plaster ceiling has molded decorations, including a motif of the collector's monogram. Fourteen lighting fixtures, covered in gold leaf, hang from the ceiling. It is normally closed to the public but can be rented for events.

The manager's office is next to the collector's office and is decorated with plain plaster walls, topped by a cornice in the Ionic order. The northeastern corner contained the cashier's office, which contained a white-marble countertop with a bronze screen. The southern half of the cashier's room has white-marble walls and was originally where members of the public conducted their transactions. The northern half, where the cashiers themselves worked, has plaster walls. The ornate plasterwork ceiling is decorated to resemble Renaissance "boxed beams", while the marble floor has a geometric border. The former cashier's office has been incorporated into the Heye Center's museum store.

The elliptical rotunda, within the building's interior courtyard, measures 85 by 135 feet (26 by 41 m) and rises to the third story. The walls and floors are composed of geometric marble tiles in several hues. The ceiling is self-supporting, without any interior metal structure, using the Guastavino tile arch system created by Spanish architect Rafael Guastavino. It consists of numerous layers of fireproof tiles, each of which measures 6 by 12 inches (15 cm × 30 cm) and has a thickness of 1 inch (2.5 cm). The tiles and layers are bonded using Portland cement. The center of the ceiling is occupied by a 140-short-ton (130-metric-ton) oval skylight. The underside of the ceiling contains eight trapezoidal panels, as well as eight long, narrow panels between them. The panels contain fresco-secco murals, which Reginald Marsh painted in 1937 with the help of eight assistants. The larger murals portray shipping activity in the Port of New York and New Jersey, while the smaller murals depict notable explorers of the New World and the Port of New York. The rotunda can be rented for special events.

The ground story is 20 feet (6.1 m) tall. Near the building's south end is space formerly used by the United States Postal Service, located around a west-east corridor accessed by both State and Whitehall Streets. There are also two ramps for delivery vehicles. The floor surface, wainscoting, and pilasters are made of marble, and the ceilings are 17 feet (5.2 m) high. When the post office was in operation, mail arrived through the delivery docks and was sorted in the basement. About 6,000 square feet (560 m2) of storage space on the ground floor, under the rotunda, was converted in 2006 to the George Gustav Heye Center's Diker Pavilion for Native Arts and Cultures. This pavilion consists of a slightly-sloped circular space seating 400 people, surrounding a maple dance floor.

The upper stories contain office space. The outer portion of the fifth story was initially used for document storage; the windows are small apertures within the entablature, making that story unsuitable for office use. The ceilings of the upper stories are between 12 and 16 feet (3.7 and 4.9 m) tall.

The United States Customs Service had been formed in 1789 with the passage of the Tariff Act, which authorized the collection of duties on imported goods. The Port of New York was the primary port of entry for goods reaching the United States in the 19th century and, as such, the New York Custom House was the country's most profitable custom house. Import taxes were a major revenue stream for the federal government before a national income tax was implemented in 1913 with the passage of the 16th Amendment. The New York Custom House had supplied two-thirds of the federal government's revenue at one point. Because the salary of the collector was tied to the custom house's revenue, the New York Custom House's collector earned more than the U.S. president, and the position was extremely powerful.

The New York Custom House had occupied several sites in Lower Manhattan before the Alexander Hamilton Custom House was built. The first such house was established in 1790 at South William Street. The custom house moved to the Government House on the site of Fort Amsterdam in 1799. The old Government House was demolished in 1815, and the site was later developed with the houses of several wealthy New Yorkers. Meanwhile, the custom house moved to numerous locations; its last location prior to the construction of the Alexander Hamilton Custom House was 55 Wall Street, which it had occupied since 1862. The custom house's Wall Street location had been optimal during the mid-19th century because it was close to the Subtreasury at 26 Wall Street, thereby making it easy to transport gold.

In February 1888, William J. Fryer Jr., superintendent of repairs of New York City's federal government buildings, wrote to the United States Department of the Treasury's Supervising Architect about the "old, damp, ill-lighted, badly ventilated" quarters there. Architecture and Building magazine called the letter "worthy of thoughtful investigation". The 55 Wall Street building's proximity to the Subtreasury was no longer advantageous, as it was easier to use a check or certificate to make payments on revenue. On September 14, 1888, Congress passed an act that would allow site selection for a new custom house and appraiser's warehouse. Soon after, Fryer presented his report to the New York State Chamber of Commerce. The Chamber said in 1889: "We have not seriously considered the removal of the present Custom House proper, since it is well located, and, if found inadequate, can easily be easily be enlarged to meet all the wants of the Government for an indefinite time to come."

Fryer recommended Bowling Green as his first preference for a new custom house, followed by a site immediately south, along State Street north of Battery Park. In September 1889, Treasury secretary William Windom selected Bowling Green as the new site of the custom house and appraiser's warehouse. Almost immediately, problems arose with the selection: Windom was accused of exceeding his authority in selecting the new site, city businessmen opposed moving the custom house, and a judge ruled in 1891 that the federal government could not take the Bowling Green site by eminent domain as it had proposed to do. A bill to acquire land for a new New York City custom house and sell the old building was passed in both houses of the U.S. Congress in early 1891.

By July 1892, a cost appraisal for acquiring the Bowling Green site was completed. The appraisal estimated that it would cost $1.96 million to acquire land at Bowling Green (about $52 million in 2020). Still, in January 1893, there was not enough money to purchase the lots at Bowling Green. The lessees and landowners were supposed to receive $2.1 million (equivalent to $56 million in 2020), but there was only $1.5 million on hand (equivalent to $40 million in 2020). The 1891 bill had allowed up to $2 million for land acquisition and had required that the previous building be sold for at least $4 million. As such, no progress was made until 1897, when a further appropriation was proposed. The proposed disbursements that would have gone to the landowners instead remained in the Treasury. An alternate site in the West Village was chosen for the appraiser's warehouse.

Architectural writer Donald Reynolds wrote that the new custom house was to be as modern as possible, with "an architectural style that embodied the tradition of the customs service, the federal government, and the United States with the latest building technology". The Tarsney Act, passed in 1893, permitted the Supervising Architect to host a competition to hire private architects to design federal-government buildings. However, the act did not take effect until Treasury secretary Lyman J. Gage took office in 1897. Furthermore, it was difficult for the federal government to sell the old building for the required price of $4 million (about $106 million in 2020). The new New York Custom House building was only the fourth building to be built under the Tarsney Act.

Republican Party officials wished to have the exclusive privilege of spending immense amounts on the new custom house building. Originally, the Chamber of Commerce and many business interests advocated for erecting a new custom house on the Wall Street site, even though it was less than half the size of the proposed Bowling Green site. In 1897, senator Thomas C. Platt and representative Lemuel E. Quigg, both Republicans, proposed bills in the United States Senate and House of Representatives for building a new custom house at Wall Street, with Platt's bill calling for a five-person commission to oversee the process. The bills died at the end of the 54th United States Congress in March 1897. The next February, during the 55th Congress, Platt and Quigg proposed bills to acquire the Bowling Green site, providing $5 million (about $136 million in 2020) for land acquisition and construction. The U.S. House and Senate passed the Bowling Green bills in March 1899. At the time, most of the structures on the site were three-story houses used by steamship offices; by April, agreements had been made with most of the sixteen landowners. The federal government disbursed $2.2 million (about $59 million in 2020) to landowners at the Bowling Green site that June. Two months later, the old Custom House was sold for $3.21 million (about $87 million in 2020).

Twenty firms were invited in May 1899 to submit designs to the competition under the terms of the Tarsney Act. The government stipulated that any plan consist of a ground-level basement and up to six stories, as well as a southward-facing light court above the third story. A committee of three men was appointed to look over the submissions. By September 1899, there were two finalists: New York City firm Carrere & Hastings and Minnesota architect Cass Gilbert. After a plan for the two finalists to collaborate failed, Supervising Architect James Knox Taylor picked Gilbert, who had been his partner at the Gilbert & Taylor architecture firm in St. Paul, Minnesota. The selection of Gilbert was controversial, drawing opposition from Platt and several other groups. Some of the opposition centered around the fact that Gilbert was a "westerner" who had newly arrived to New York City, and several opponents raised doubts about the jury's competence. After Gage certified Gilbert's selection in November 1899, the opposition decreased significantly.

Demolition of existing buildings on the site began in February 1900, and by that August, test bores were being made for the construction of the new Custom House's foundations. Isaac A. Hoppes received a contract for such work the same December. The site was excavated to a depth of 25 feet (7.6 m), and some 2.2 million cubic feet (62,000 m3) of dirt was removed. The New-York Tribune called the site "the biggest hole that was ever made in this city over which to erect a building". In December 1901, the federal government accepted contractor John Peirce's bid to erect the Custom House building's first floor. Pending further appropriations, the rest of the building would also be built by Peirce. At the time, there was only $3 million budgeted toward the Custom House's completion (equal to $77 million in 2020). The following November, Peirce was authorized to complete the remaining stories, after another $1.5 million (equal to $38 million in 2020) was allocated to continue construction.

The cornerstone of the building was laid on October 7, 1902, in a ceremony attended by Treasury secretary Leslie M. Shaw. After a ticker tape parade down Broadway, the cornerstone, filled with contemporary souvenirs and artifacts, was placed at the northeast corner of the site. The new Custom House's construction lagged due to government bureaucracy, while work on comparable private buildings nearby proceeded more quickly. The slow construction was attributed to various reasons, such as concurrent jobs being undertaken by the building's contractors, money shortages, and lack of supplies. Nonetheless, the building's imminent completion sparked the development of other nearby sites. The Custom House was reportedly 70 percent complete by February 1905, according to Peirce. That September, J. C. Robinson was contracted to furnish the interior of the building. With a proposed final cost of $4.5 million (approximately $100 million in 2020), it was to be more expensive than every other public building in New York City except for the Tweed Courthouse.

A branch of the United States Postal Service moved to the Bridge Street side of the building's ground floor in July 1906, becoming the first tenant to occupy the building. The same year, an additional $465,000 was allocated for the building's completion (equivalent to $10 million in 2020). By September 1907, the Custom House was ready to open. The next month, the building was formally declared completed and the contractors turned over the building to the federal government. At the time, most of the internal furnishings had not been added. The U.S. Customs Service moved its offices to Bowling Green on November 4, 1907.

Following the Customs Service's relocation to the Custom House, other government agencies with offices in New York City, such as the Weather Bureau, also moved to the Bowling Green Custom House. By 1908, the Custom House was fully occupied by these other agencies, as the Treasury's chief architect had assigned space to other departments without consulting with the collector. The next year, the House of Representatives approved the installation of a pneumatic-tube system so the post office and custom house could send packages to the appraiser's warehouse. In 1918, following the U.S. entry into World War I the previous year, Gilbert was directed to remove all references to Germany from the Custom House's sculptures, since Germany was one of the Central Powers against which the United States was fighting. The German insignia on the entablature's Germania statue was accordingly replaced with those of Belgium. The next year, the U.S. Passport Agency moved to the Custom House building.

In 1937, during the Great Depression, the Treasury Relief Art Project (with funds and assistance from the Works Projects Administration) commissioned a cycle of murals for the main rotunda from Reginald Marsh. The ceiling of the rotunda had been undecorated white plaster when the building was first erected. By 1940, officials were asking that the Custom House be renovated. Then-collector Harry M. Durning requested at least $190,000 from Congress, saying that "men [were] falling out of ancient chairs, and [...] our valuable records and current papers stacked on desks and improperly filed in decrepit cabinets and bookshelves". From 1914 to 1956, the Bowling Green Custom House also included a regional tax office, where companies and residents in Manhattan south of 34th Street had to pay their taxes.

As early as 1964, the U.S. Customs Service considered moving to the World Trade Center, which was under construction. The Customs Service signed a long-term lease with the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey at Six World Trade Center in 1970. The Customs Service moved in 1973. At the time, the New York Custom House had 1,375 employees, and the land under the building was estimated to be worth between $15 million and $20 million (about $68–91 million in 2020). The General Services Administration (GSA) acquired the Bowling Green Custom House after the Customs Service relocated.

From 1974 on, the Custom House was vacant, and different parts of the building fell into various states of disrepair. Marsh's ceiling murals and the commissioner's room remained relatively intact, but there was peeling paint in other offices, and weeds were growing from the statues outside. The nonprofit organization Custom House Institute was founded in 1974 to preserve the building; the next year, the federal government declared the building as "surplus" property, thereby making it available to the city government. The architect I. M. Pei suggested converting the upper floors into office space, keeping the second-floor rotunda open, and converting the first floor to commercial use. This did not happen, and the Custom House Institute occupied the first floor while the GSA cleaned the facade; the upper six floors remained unused. These stories were seldom open to the public except for special events. These included the bicentennial of the United States in 1976, a summer arts program in 1977, and another arts exhibition in 1979.

The GSA estimated in 1977 that it would cost $24 million to renovate the Bowling Green Custom House (about 82 million in 2020). The building's preservation was spurred by U.S. senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan, who gave U.S. House representatives a tour of the building to convince them to fund its renovation. In 1979, in part because of his advocacy, Congress approved a $26.5 million budget for the renovation, including the restoration of Marsh's murals. The GSA hosted a request for proposals in 1983, soliciting tenants for 77,000 square feet (7,200 m2) in the Custom House. Six plans for the building's reuse were presented to Manhattan Community Board 1 in August 1984. Among those, two plans were considered most seriously: one for a Holocaust museum and the other for a cultural and educational center with an ocean liner museum, restaurants, and theaters. Of these, the community board's members was overwhelmingly in favor of the cultural and educational center, while Jewish groups preferred the Holocaust museum. The Holocaust museum proposal was selected in October 1984. The Museum of Jewish Heritage, as the museum would be known, accepted an alternate site nearby at Battery Park City two years later, after preservationists said it would be "inappropriate" for such a museum to be located in the Custom House.

An $18.3 million renovation (equivalent to 39 million in 2020) began in August 1984. Exterior and ceremonial interior spaces were cleaned, restored, and conserved. Old office space was renovated for federal courtrooms and ancillary offices; rental offices and meeting rooms; and a 350-seat auditorium. The building's fire-safety, security, telecommunications, and heating, ventilation, and air conditioning systems were also upgraded. Ehrenkrantz and Eckstut Architects undertook the project.

By early 1987, Moynihan was proposing legislation that would turn over the building to the Museum of the American Indian (later the George Gustav Heye Center), which at the time occupied Audubon Terrace in Upper Manhattan. This led to opposition from the American Indian Community House, which wished to occupy a part of the Custom House, and which argued that the museum was run mostly by non-Indians. At the time, the Museum of the American Indian wished to relocate because its Upper Manhattan facility was insufficient, and the Custom House was being offered as an alternative for the museum's possible relocation to Washington, D.C. U.S. senator Daniel Inouye introduced the National Museum of the American Indian Act the next month, which would have brought the collection to Washington, D.C., instead. A compromise was reached in 1988, in which the Smithsonian would build its own museum in Washington, D.C. The Smithsonian would also acquire the Heye collection, which it would continue to operate in New York City at the Custom House. The act was passed in 1989.

In 1990, the building was officially renamed after Alexander Hamilton, the first Secretary of the Treasury, by act of Congress. The George Gustav Heye Center of the National Museum of the American Indian opened in the Custom House in October 1994. At that time, most of the space had been closed for 20 years. The Heye Center occupied the three lower stories, while the United States Bankruptcy Court for the Southern District of New York occupied two additional stories. The other two stories were unoccupied and had not been renovated, but the GSA planned to renovate the vacant stories.

The museum and building were mostly undamaged by the September 11 attacks in 2001, but airborne debris from the collapse of the World Trade Center had to be cleared from some of the interior spaces. The Heye Center's exhibition and public access areas originally totaled about 20,000 square feet (1,900 m2). The museum expanded into part of the ground floor in 2006. Six years later, the National Archives and Records Administration offices in New York moved to the Custom House. As of 2022, U.S. Customs and Border Protection owns the Custom House.

Gilbert stated that during the design process, a tall dome was suggested in order to make the building into a "landmark" but that "this would wholly destroy the proportions of the building per se, and as a matter of plan, seriously impair its practical usefulness". Gilbert suggested that a 400-foot (120 m) storage tower would be more appropriate if a "landmark" was necessitated, but that such a tower "would add considerably to the cost".

From the start, the Alexander Hamilton Custom House was architecturally distinguished from other buildings in the area. The New York Times said in 1906 that "it is the unity of idea embodied in the new Custom House and enforced by the wealth of sculpture with which it is embellished, more than its mere costliness, that gives to the edifice its unique value". A Times editorial the same year said that, despite the federal government's initial reluctance to decorate the Custom House lavishly, "few recall the money sunk into stone, bricks and mortar; they enjoy the final touches inside on which millions were not squandered". The Wall Street Journal wrote in 1914 that the Custom House "represents the national Government in its economic bases and financial life".

Critical acclaim for the building continued in the decades after its completion. Architectural writer Henry Hope Reed Jr. regarded the Custom House in 1964 as "the finest public building in New York". When the U.S. Customs Service relocated in 1973, Ada Louise Huxtable wrote that 6 World Trade Center's "functional, featureless grid" contrasted with the "splendor" of the Alexander Hamilton Custom House. Architectural writer Robert A. M. Stern stated in his 1983 book New York 1900 that the Custom House and the Ellis Island immigration station were the two structures that reinforced New York City's role as "the leading American metropolis, representative of America's role in the world".

The Custom House was one of the earliest designations of the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission, becoming an official exterior landmark in October 1965, six months after the commission's founding. At the time of the exterior designation, the commission said that "At some time in the future this building may be in jeopardy", since the federal government had doubted whether the Custom House should be made a city landmark. The Custom House's interior was also designated an official city landmark in January 1979. The building was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1972, the designation covering both its exterior and public interior spaces. The site was also declared a National Historic Landmark in 1976. In 2007, it was designated as a contributing property to the Wall Street Historic District, a NRHP district.

A stock certificate is issued by businesses, usually companies. A stock is part of the permanent finance of a business. Normally, they are never repaid, and the investor can recover his/her money only by selling to another investor. Most stocks, or also called shares, earn dividends, at the business's discretion, depending on how well it has traded. A stockholder or shareholder is a part-owner of the business that issued the stock certificates.

Ebay ID: labarre_galleries