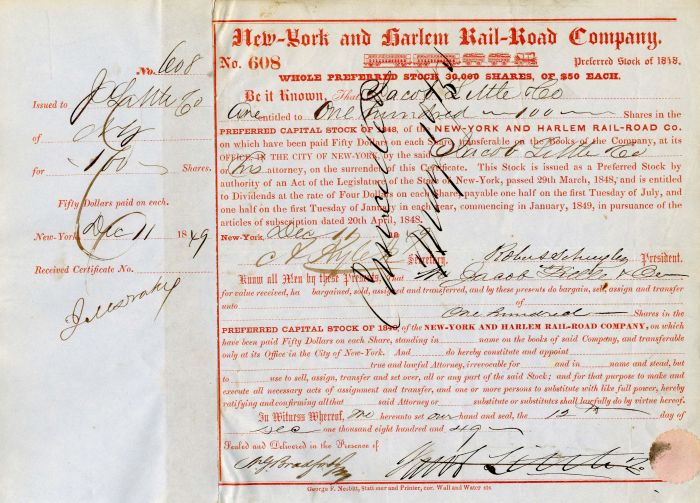

New-York and Harlem Rail-Road Co. signed by Jacob Little and Robert Schuyler - Stock Certificate

Inv# AG1076B Stock

Stock signed by Jacob Little for his company. Also signed by Robert Schuyler. Very Rare!

Twelve years of industry, integrity, and energetic devotion to business placed Mr. Little at the head of financial operations on Wall Street. He identified himself with the style of business known as " Bearing Stocks." He was called the Great Bear on 'change. His mode of business enabled him to roll up an almost untold fortune. He held on to his system till it hurled him down and beat him to pieces. For more than a quarter of a century Mr. Little's office in the old Exchange building was the centre of daring, gigantic speculations. On change his tread was that of a king. He was rapid and prompt in his dealings, and his purchases were usually made with great judgment. He controlled so large an amount of stock that he was called the Napoleon of the Board. When capitalists regarded railroads with distrust, he put himself at the head of the railroad movement. He comprehended the profit to be derived from their construction. In this way he rolled up an immense fortune, and was known everywhere as the Railway King. He was the first-to discover when the business was overdone, and immediately changed his course. At this time the Erie was a favorite stock, and was selling at par. Mr. Little contracted to sell a large amount of this stock, to be delivered at a future day. His rivals on Wall Street, anxious to floor him, formed a combination. They took all the contracts he offered, bought up all the new stock, and placed everything out of Mr. Little's reach, making it, as they thought, impossible for him to carry out his contracts. His ruin seemed inevitable, as his rivals had both his contract and the stock. The morning dawned when the stock must be delivered, or the Great Bear of Wall Street break. At one o'clock he entered the office of the Erie company. He presented certain certificates of indebtedness which had been issued by the corporation. By those certificates the company had covenanted to issue stock in exchange. That stock Mr. Little demanded. Nothing could be done but to comply. With that stock he met his contract, floored the conspirators, and triumphed.

Walking from Wall Street with a friend one day they passed through Union Square, then the abode of our wealthiest people. Looking at the rows of elegant houses, Mr. Little remarked, "I have lost money enough today to buy this whole square. Yes," he added, "and half the people in it." Three times he became bankrupt. In each failure he recovered, and paid his contracts in full. It was a common remark among the capitalists, that " Jacob Little's suspended papers were better than the checks of most men." His personal appearance was commanding. He was tall and slim; his eye expressive; his face indicated talent; the whole man inspired confidence. He was retiring in his manner, and quite diffident except in business. He was generous as a creditor. If a man could not meet his contracts, and Mr. Little was satisfied that he was honest, he never pressed him. After his first suspension, though legally free, he paid every creditor in full, though it took nearly a million dollars.

He was a devout member of the Episcopal Church. his charities were large, unostentatious, and limited to no sect. The Southern Rebellion swept away his remaining fortune, yet, without a murmur, he laid the loss on the altar of his country. He died in the bosom of his family. His last words were, * I am going up. Who will go with me ? "

Robert Schuyler Few chieftains of American finance have fallen as far and as fast as Robert Schuyler. In the early 1850s Schuyler achieved fame as “America’s first railroad king,” then infamy as the perpetrator of its first massive stock fraud. By 1853 he had been president of five roads—the Illinois Central, New York and Harlem, New York and New Haven, Renssalaer and Saratoga, and Sangamon and Morgan—most of them simultaneously; he had been instrumental in building the Vermont Valley and the Washington and Saratoga, and in the promotion and administration of the Housatonic, Naugatuck, New Haven and Northampton, and Saratoga and Whitehall. A scion of a blue-blooded New York family that counted Alexander Hamilton among its ancestors, he was widely admired and trusted. Ironically, it was Schuyler’s wide-ranging involvements that proved his undoing. In his capacity as transfer agent of the New York and New Haven, beginning in October 1853 he issued some $2 million in unauthorized stock, diverting the proceeds to other railroad ventures he was juggling. In the past he had covered up similar over-issues on a much smaller scale by buying back and retiring the over-issued shares. This time, though, events spun out of his control; the irregularities became public at the beginning of July 1854, Schuyler fled to Canada under threat of arrest, then to Europe, where he died in disgrace in November 1855. Schuyler’s defalcations were genuinely sensational, sending shock waves through the realms of finance and high society; one contemporary reaction was that the “Schuyler fraud fell like a thousand bombshells, or hissed like a million fiery flying serpents in Wall-street,” and a newspaper editorialized, “if Robert Schuyler is capable of such a wrong, then no one is to be trusted.” The New York and New Haven would eventually lose nearly $1.8 million redeeming the spurious stock. So strong was society’s condemnation that the Schuyler’s name was virtually excised from the historical record for decades.

A stock certificate is issued by businesses, usually companies. A stock is part of the permanent finance of a business. Normally, they are never repaid, and the investor can recover his/her money only by selling to another investor. Most stocks, or also called shares, earn dividends, at the business's discretion, depending on how well it has traded. A stockholder or shareholder is a part-owner of the business that issued the stock certificates.

Ebay ID: labarre_galleries