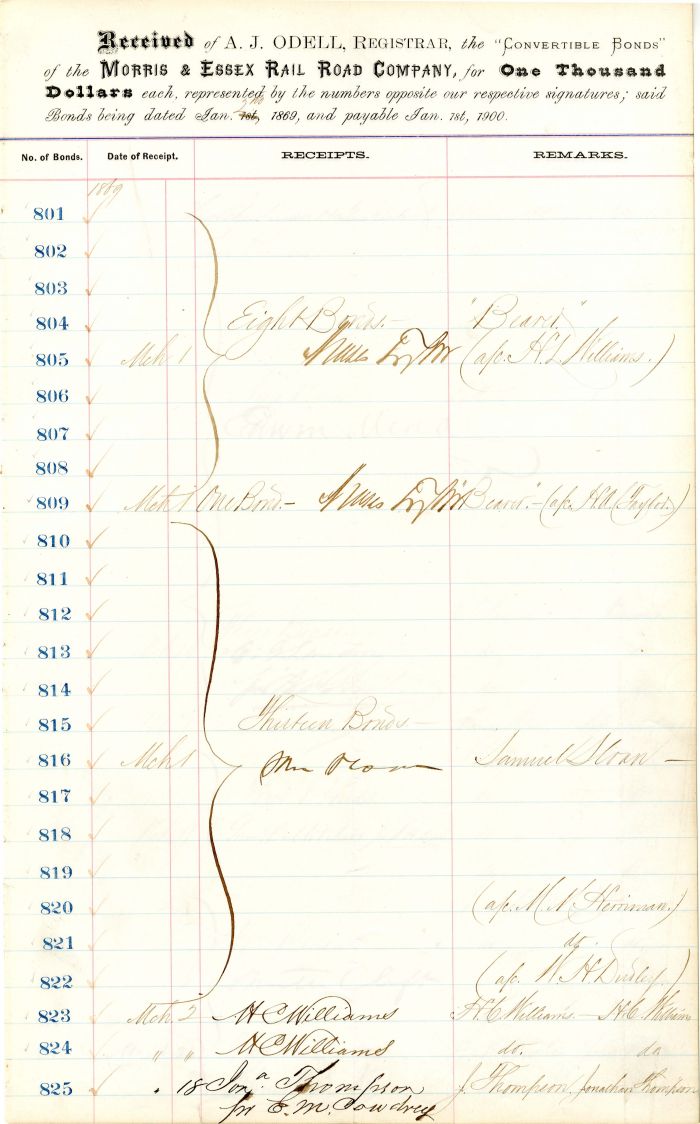

Morris and Essex Rail Road Co. Ledger Sheet signed by Moses Taylor

Inv# AG1960

Ledger Sheet of the Morris & Essex Rail Road Company signed twice by Moses Taylor. Also signed by Samuel Sloan.

Moses Taylor (January 11, 1806 – May 23, 1882) was a 19th-century New York merchant and banker and one of the wealthiest men of that century. At his death, his estate was reported to be worth $70 million, or about $1.9 billion in today's dollars. He controlled the National City Bank of New York (later to become Citibank), the Delaware, Lackawanna & Western railroad, and the Moses Taylor & Co. import business, and he held numerous other investments in railroads and industry.

Taylor was born on January 11, 1806 to Jacob B. Taylor and Martha (née Brant) Taylor. His father was a close associate of John Jacob Astor and acted as his agent by purchasing New York real estate while concealing Astor's interest. Astor's relationship with the Taylor family provided Moses with an early advantage.

At age 15, Moses Taylor began working at J. D. Brown shippers. He soon moved to a clerk's position in the firm of Gardiner Greene Howland and Samuel Howland's firm G. G. & S. Howland Company of New York, a shipping and import firm that traded with South America.

By 1832, at age 26, Moses had sufficient wealth to marry, leave the Howland company, and start his own business as a sugar broker. As such he dealt with slave-owning Cuban sugar growers, found buyers for their product, exchanged currency, and advised and assisted them with their investments. He nurtured relationships with those slave-owners, who relied on him for loans and investments to support their plantations. Taylor never visited Cuba, but his friendship with Henry Augustus Coit, a prominent trader who was fluent in Spanish, enabled him to trade with the Cuban growers. Taylor soon discovered that loans and investments provided returns that were as good as, or better than, those from the sugar business, although the sugar trade remained a core source of income. By the 1840s his income was largely from interest and investments. By 1847, Moses Taylor was listed as one of New York City's 25 millionaires.

When the Panic of 1837 allowed Astor to take over what was then City Bank of New York (today known as Citibank), he named Moses Taylor as director. Moses himself had doubled his fortune during the panic, and brought his growing financial connections to the bank. He acquired equity in the bank and in 1855 became its president, operating it largely in support of his and his associates' businesses and investments.

In the 1850s Moses invested in iron and coal, and began purchasing interest in the Delaware, Lackawanna & Western railroad. When the Panic of 1857 brought the railroad to the brink of bankruptcy, Moses obtained control by purchasing its outstanding shares for $5 a share. Within seven years the shares became worth $240, and the D. L. & W was one of the premier railroads of the country. By 1865 Moses held 20,000 shares worth almost $50 million.

Moses held an interest in the New York, Newfoundland, and London Telegraph Company that Cyrus West Field had founded in 1854. Although its attempts to lay a cable across the Atlantic were initially unsuccessful, it eventually succeeded and in 1866 became the first transatlantic telegraph company.

Taylor also had controlling interest in the largest two of the seven gas companies in Manhattan that were merged (after his death) to form the Consolidated Gas Company in 1884, eventually becoming Consolidated Edison. Taylor's Manhattan Gas Company and New York Gas Light Company were 45% of the merged Consolidated Gas, and his descendants remained some the largest individual shareholders of Consolidated Edison.

After the Civil War, during which he assisted the Union with financing the war debt, he continued to invest in iron, railroads, and real estate. His real estate holdings in New York brought him into close association with Boss Tweed of New York's Tammany Hall. Moses sat in 1871 on a committee made up of New York's most influential and successful businessmen and signed his name to a report that commended Tweed's controller for his honesty and integrity. This report was considered a notorious whitewash.

Taylor was married to Catharine Anne Wilson (1810–1892). Together, they were the parents of:

- Albertina Shelton Taylor (1833–1900), who married Percy Rivington Pyne (1820–1895) in 1855. Pyne, an assistant to Moses, became president of City Bank upon Moses' death.

- Mary Taylor (1837–1907), who married George Lewis (1833–1888)

- George Campbell Taylor (1837–1907)

- Katherine Wilson Taylor (1839–1925), who married Robert Winthrop

- Henry Augustus Coit Taylor (1841–1921), who married Charlotte Talbot Fearing (1845–1899) in 1868. After her death, he married Josephine Whitney Johnson (1849–1927) in 1903. Taylor left an estate worth $50 million upon his death in 1921, just a few months before the death of his nephew Moses Taylor Pyne.

Moses died in 1882 and although he owned a vault at the New York City Marble Cemetery that already contained members of his family, he was buried in Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn, New York City. Moses left his fortune to his wife and children. Many of the Taylor family descendants were prominent in New York and Newport society and several prominent families owe a substantial portion of their fortunes to the Taylor inheritances.

Through his daughter Albertina, the Pynes family became a dynasty of bankers that survives to this day. Percy's son Moses Taylor Pyne was a benefactor of Princeton University who supported its development from a college into a university and left an estate worth $100 million at his death in 1921.

Through his daughter Katherine, he was a grandfather of Hamilton Fish Kean (1862–1941), ancestor of the political Kean family which includes the former governor of New Jersey Thomas Kean.

Not noted for philanthropy during his life, at its end in 1882 Moses Taylor donated $250,000 to build a hospital in Scranton, Pennsylvania to benefit his iron and coal workers, and workers of the D. L. & W railroad. The Moses Taylor hospital continues in operation today.

Samuel Sloan (1817-1907) Samuel Sloan was a well known 19th century railroad executive. He was a son of William and Elizabeth Sloan of Lisburn, County Down, Ireland. When he was a year old he was brought by his parents to N.Y. At age 14, the death of his father compelled Samuel to withdraw from the Columbia College Preparatory School, and he found employment at an importing house on Cedar Street in N.Y., where he remained connected for 25 years, becoming head of the firm. On April 8, 1844, he was married to Margaret Elmendorf, and took up his residence in Brooklyn. He was chosen a supervisor of Kings County in 1852, and served as president of the Long Island College Hospital. In 1857, having retired from the importing business, he was elected as a Democrat to the New York State Senate, of which he was a member for two years. Sloan at 40 was recognized in New York as a successful businessman who had weathered two major financial panics, but it could hardly have been predicted that 20 years of modest achievement as a commission merchant would be followed by more than forty years in constructive and profitable effort in a wholly different field—that of transportation.

As early as 1855 he had been a director of the Hudson River railroad. Election to the presidency of the road quickly followed, and in the 9 years that he guided its destinies, the market value of the company’s shares rose from $17 to $140. Resigning from the Hudson River, he was elected, in 1864, a director, and in 1867, president, of the Delaware, Lackawanna & Western Railroad, then and long after known as one of the small group of “coal roads” that divided the Pennsylvania anthracite territory. Beginning in the reconstruction and expansion era following the Civil War, Sloan’s administration of 32 years covered the period of shipping rebates, “cut-throat” competition, and hostile state legislation, culminating in federal regulation through the Interstate Commerce Commission. Sloan’s immediate job, as he saw it, was to make the Lackawanna more than a “coal road,” serving a limited region. Extensions north and west, and, finally, entrance into Buffalo, made it a factor in general freight handling. Readjustments had to be made. It was imperative, for example, that the old gauge of six feet be shifted to the standard 4’8 1/2". This feat was finally achieved on May 25, 1876, with a delay of traffic of only 24 hours—in some cases less. The total cost of the improvement was $1,250,000.

Sloan was an ally of J. P. Morgan, and one of the founders of what is now Citibank and his name is engraved in stone on the wall in the former Citibank headquarters at 55 Wall Street. There is a statute of Sam Sloan one block from the former Lackawanna Railroad station in Hoboken, New Jersey. Sam Sloan had little patience with the likes of Jay Gould and Jim Fiske, and the other 19th-century “robber barons.” In his book, “Reminiscences of a Stock Broker,” Edwin Lefere, wrote: “The newspapers never had to beat about the bush with old Sam Sloan.” Although Sloan resigned the presidency in 1899, he continued for the remaining 8 years of his life as chairman of the board of directors. At his death, at the age of 90, he had been continuously employed in railroad administration for more than half a century and had actually been the president of 17 corporations. At the time of his death he was director or officer of 33 corporations including Citibank, Farmers Loan and Trust Co., United States Trust Co., Consolidated Gas Co., and Western Union Telegraph Company.

The Morris and Essex Railroad was a railroad across northern New Jersey, later part of the main line of the Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railroad.

The M&E was incorporated January 29, 1835, to build a line from Newark in Essex County west to and beyond Morristown in Morris County. The first section, from Newark west to Orange, opened on November 19, 1836. Under an agreement signed on October 21, the New Jersey Rail Road provided connecting service from Newark east to Jersey City via the Bergen Hill Cut. The original connection between the two lines was in downtown Newark; the M&E turned south on Broad Street to meet a branch of the NJRR at Market Street. Service to Paulus Hook in what is today Jersey City commenced on October 14, 1836 and passengers could transfer to the Jersey City Ferry and cross to lower Manhattan at the nearby ferry slips.

On January 1, 1838, the M&E was extended their route to Morristown. On October 29 of that year, an agreement was signed to move the NJRR connection to the foot of Centre Street (via the northeast side of Park Place, to the NJRR alignment along the Passaic River), and the track on Broad Street was removed. Through car service began August 1, 1843, with horse power used along the streets, between Broad Street station and the foot of Centre Street.

Continuations opened west to Dover on July 31, 1848, Hackettstown in January 1854, and the full distance to Phillipsburg in 1866.

A new alignment, including a bridge over the Passaic River, was built by the NJRR and opened on August 5, 1854, ending at East Newark Junction with the NJRR main line in Harrison. This eliminated the street running in downtown Newark; those tracks were removed the next year after a lawsuit was filed by Newark.

On March 6, 1857, a supplement to the M&E charter was passed, authorizing it to buy the new alignment (until then owned by the NJRR as their East Newark Branch) and build a new line to Jersey City, as long as it passed under Bergen Hill in a tunnel. With this authority, the M&E became important as a possible competitor to the NJRR, and began negotiations with the Camden and Amboy Railroad. The New Brunswick, Millburn and Orange Railroad was proposed as a connection between the two, allowing for a C&A route to Jersey City without using the NJRR.

The Hoboken Land and Improvement Company operated a ferry across the Hudson River between Hoboken and New York City. Until early 1859 the NJRR paid the HL&I for the business that instead used the NJRR ferry. Because of this, the HL&I decided to help the M&E by building their new alignment, using the New York and Erie Railroad's Long Dock Tunnel. To use the Erie's tunnel a supplement to their charter was needed; this was passed March 8, 1860 after arguments against the bill from the NJRR. Another legal obstacle was the NJRR's monopoly over bridges, granted to the Passaic and Hackensack Bridge Company, invalidated by the state in 1861. The first excursion train operated on the new alignment on November 14, 1862, but a contract required the M&E to continue using the NJRR until October 13, 1863. The next day, regular service began via the new alignment.

On November 1, 1865, the Atlantic and Great Western Railway leased the M&E as part of its planned route to the west. However, the A&GW went bankrupt in 1867 and the lease was cancelled. The Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railroad leased the M&E on December 10, 1868, connecting to their Warren Railroad at Washington.

In 1868 the Morris & Essex leased the Newark and Bloomfield Railroad, which connected Roseville Avenue to Bloomfield and Montclair, then West Bloomfield.

In 1876 the new tunnel under Bergen Hill opened, after hostilities including a frog war in late 1870 and early 1871, caused by the M&E's attempts to modify the connection between their Boonton Branch, a newer freight bypass, and the Erie tunnel.

The DL&W built the New Jersey Cut-Off, a long low-grade bypass in northwestern New Jersey, opened in 1911 from the M&E at Port Morris west to Slateford Junction just inside Pennsylvania.

On July 26, 1945 the M&E was formally merged into the DL&W. However it remained the Morris and Essex Division, and even today New Jersey Transit calls it the Morris and Essex Lines. In 1960 the DL&W merged with the Erie Railroad to form the Erie-Lackawanna Railroad, becoming part of Conrail in 1976.

Stations

- New York (Foot of Barclay Street)

- New York (Foot of Christopher Street) (ferry)

- Hoboken (MP 1.25) (ferry)

- West End (MP 3.25)

- Seaboard (MP 5)

- Kearny Junction (MP7.0)

- Harrison (MP 9)

- Newark (MP 10) - Junction Newark and Bloomfield Railway

- Roseville, Avenue (MP 11.0)

- East Orange (MP 12)

- Brick Church (MP 13)

- Orange (MP 13)

- Highland Avenue (MP 14)

- Mountain Station (MP 15)

- South Orange (MP 16)

- Maplewood (MP 17)

- Millburn (MP 19)

- Short Hills (MP 20)

- Summit (MP 22)

- Chatham (MP 26)

- Madison (MP 28)

- Convent (MP 30)

- Morristown (MP 32)

- Morris Plains (MP 34)

- Mount Tabor (MP 38)

- Denville (MP 38) - Junction with Boonton Branch

- Rockaway (MP 40)

- Dover (MP 43) - Junction with Chester Railway

- Wharton (MP 44)

- Chester Junction (MP 45)

- Lake Junction (MP 45) - Junction with Central Railroad of New Jersey

- Mount Arlington (MP 47)

- Drakesville (MP 48)

- Lake Hopatcong (MP 49)

- Port Morris Junction (MP 50)

- Port Morris (MP 51)

- Sussex Branch Junction (MP 53)

- Netcong/Stanhope (MP 53)

- Waterloo (MP 56) - Junction with Sussex Railroad of New Jersey

- Hacketttstown (MP 62)

- Port Murray (MP 67)

- Washington (MP 71) - Junction with Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railroad

- Broadway (MP 76)

- Stewartsville (MP 80)

- Phillipsburg Union Station (MP 85)

- Easton (MP 85), - Junction with Lehigh Valley Railroad, Central Railroad of New Jersey, and the Lehigh and Susquehanna Railroad

Branches

The Boonton Branch was first built as a short branch from the main line at Denville east to Boonton. It was later extended much further east toward Paterson to return to the main line at the west end of Bergen Hill; this opened on September 17, 1870. A realignment was later built at the west end, bypassing Denville and some curves, for a shortcut of both the branch and the main line. In 1903 the Kingsland Tunnel opened as part of a short realignment at Kingsland. The Harrison Cut-Off was also built around this time as a connection from the Boonton Branch at Kingsland south to the main line in Kearny.

The Morris and Essex Extension Railroad was chartered in 1889 and opened later that year, connecting the Boonton Branch to Paterson.

The Newark and Bloomfield Railroad was chartered in 1852 and opened in 1855 as a short branch from the main line at Roseville Avenue/Bloomfield Junction northwest to Montclair via Bloomfield. It was built by the M&E and mostly owned by them. The M&E leased it on April 1, 1868.

The New Jersey West Line Railroad was a failed plan to build a new line across the state; only the part from Summit on the M&E west to Bernardsville was completed, and it was soon renamed the Passaic and Delaware Railroad. The DL&W leased it on November 1, 1882 as a branch of the M&E. The Passaic and Delaware Extension Railroad was chartered in 1890 and opened later that year, extending the line to Gladstone.

The Chester Railroad was incorporated in 1867 and opened in 1872, running from the M&E west of Dover southwest to Chester.

The short Hopatcong Railroad was a branch from the M&E at Hopatcong north to Roxbury. The DL&W bought it in 1892.

The Sussex Railroad stretched north from the M&E at Waterloo (later Stanhope) to Newton and beyond. The DL&W leased it in 1924.

Ebay ID: labarre_galleries